A Dangerous Swim

On a summer day in northeastern Australia, 10-year-old Rachael Shardlow went for a swim in the Calliope River.

As she was splashing in the water with her older brother, Sam, Rachael felt something wrap around her legs. She was tangled in the tentacles of a box jellyfish! Tentacles are thin, flexible extensions that some sea creatures used to capture their prey. The jellyfish tightened its tentacles around Rachael, stinging her and injecting deadly venom, a deadly poison, into her body.

Seconds later, Rachael told her brother that she couldn’t see or breathe. Sam pulled her away from the jellyfish, ripping some of the tentacles. He carried her to their parents on the riverbank. Rachael asked her family if she was going to die, and then she passed out.

Pieces of the box jellyfish’s tentacles still clung to Rachael’s legs. A couple camping nearby knew to pour vinegar on the tentacles to prevent more stings. Vinegar is sour and has acids to help treat jellyfish stings. Because she had passed out, Rachael didn’t feel the tremendous pain that jellyfish venom causes. Rachael’s parents rushed her to the hospital. On the way, she stopped breathing and turned blue. Rachael’s father performed CPR to keep her breathing.

Two days later, Rachael woke up in the hospital. She stayed there for six weeks recovering. By that time, her injuries were no longer painful. Rachael went home with scars on her legs and some short-term memory loss, but she had survived.

Victims usually survive minor stings from box jellyfish. Experts say that Rachael is the only person to survive such serious stings. The jellyfish’s venom quickly attacks the heart and muscles. It also attacks the nervous system, which contains your brain, spinal cord, and other nerves in your body. It can kill in less than four minutes, often before the victim can be rescued from the water. A person who is badly stung rarely survives. Rachael is lucky to be alive. People call her survival a miracle.

Tentacles, Stinging Cells, and Venom

The box jellyfish is the most feared of all jellyfish. Its powerful venom makes it one of the world’s deadliest creatures. Box jellyfish live in the warm ocean waters north of Australia. They are found as far north as the Philippines. They float in calm, shallow waters near shore, especially where rivers meet the ocean. These are also popular places for people to swim.

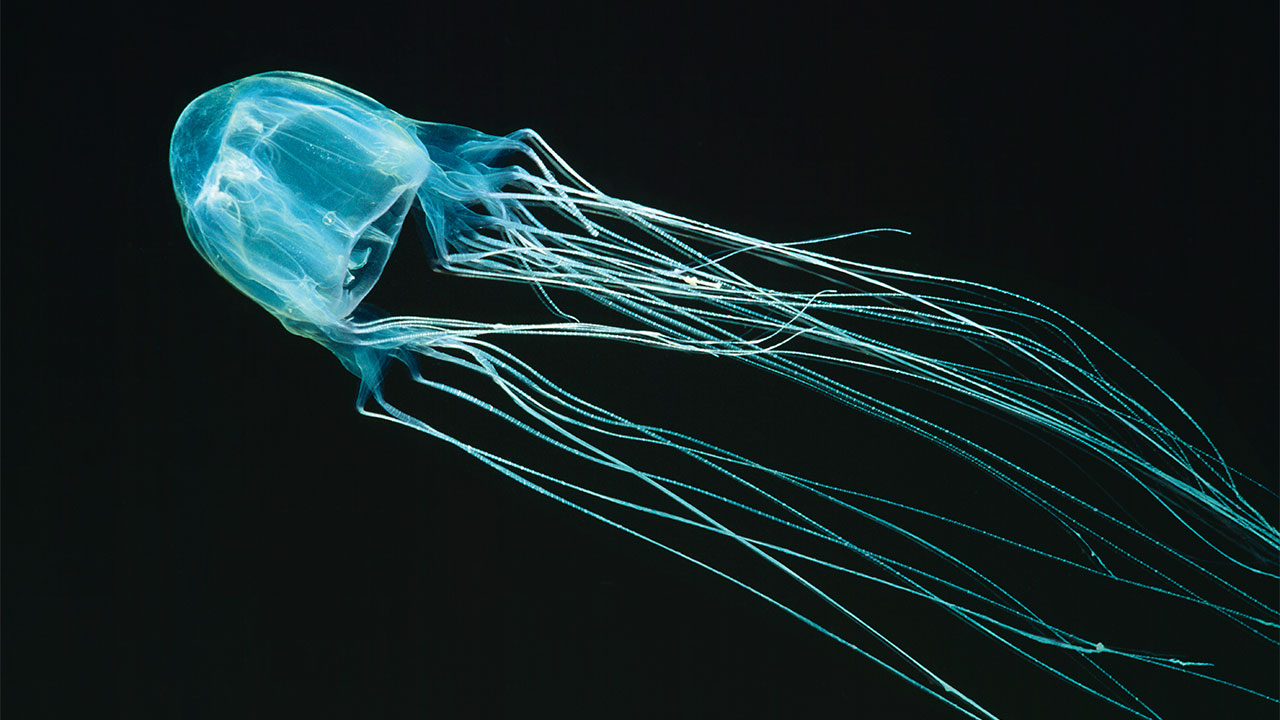

Box jellyfish have pale blue bodies. Swimmers often have trouble seeing the deadly creatures because they blend in with the water. Their transparency, or see-through, acts as camouflage, which allows them to hide and protect themselves from predators. It also helps box jellyfish surprise prey. Fish that swim into a jellyfish’s tentacles quickly become food. While most jellyfish drift with ocean currents, box jellyfish often chase their prey. They can reach a speed of 5 miles (8 kilometers) per hour.

The box jellyfish gets its name from the boxy shape of its bell, the body. The soft, smooth bell can grow to be the size of a basketball. The jellyfish does not have a head, a heart, ears, bones, blood, or legs. Its mouth is in the center of its body. Instead of a brain, the box jellyfish has a nerve net that senses changes in light or direction. The jellyfish has 24 eyes that are arranged in groups of six. Two eyes in each group work like human eyes.

However, scientists have yet to discover how box jellyfish can process what they see without a brain.

Stringy tentacles that measure up to 10 feet (3 meters) long hang from a box jellyfish’s body. As many as 15 tentacles grow from each corner of the bell. They tangle together to form a net that traps anything that swims near.

The box jellyfish uses stinging cells to defend itself and kill prey. Thousands of stinging cells cover each tentacle. Each cell contains a tiny stinger shaped like a dart. The cells fire these darts when the tentacle comes in contact with chemicals on the victim’s skin. With the brush of a single tentacle, thousands of stinging cells fire powerful venom into a victim. As the victim struggles to get away, the tentacle clings tighter and more stinging cells are triggered.

Most chance meetings with box jellyfish involve minor, treatable stings. Some encounters, however, can result in thousands of stings and a deadly amount of venom entering the victim’s body. The powerful venom starts to work right away. First, a victim feels the pain of the sting itself. Some victims die of heart failure within minutes or go into shock because of the intense pain. Venom affects victims so quickly that they often drown before they are able to swim to shore. Survivors are left with white marks on their skin. Later, these whip-like marks turn red, blister, and scar.

Preventing Stings

The best way to avoid a box jellyfish sting is to stay out of the waters in which they live. Signs posted at beaches and along rivers warn people of the danger. Some beaches protect swimmers by putting up nets that keep box jellyfish out. Swimmers, snorkelers, and scuba divers often wear stinger suits. These lightweight suits cover the entire body to keep the skin’s chemicals from triggering a jellyfish’s stinging cells.

Someone who is stung by a box jellyfish needs immediate medical attention. Help the victim out of the water and get a lifeguard or call an emergency number. The victim may need CPR if the venom has affected his or her breathing or caused heart failure. It’s also important to prevent more venom from entering the victim’s system. Pouring vinegar over the remaining tentacles will prevent the stinging cells from firing. They should be carefully washed away with saltwater or removed with gloved hands. A tool, such as a stick, shell, or tweezers, could also be used. The victim should then be taken to a hospital as quickly as possible.

In recent years, the population of box jellyfish has been on the rise. The number of reported stings has also increased. Experts believe overfishing of the ocean has driven jellyfish closer to shore to find prey.

In the coming years, climate change, long-term weather change, may also affect the population of box jellyfish. These sea animals are used to living in warm, tropical waters. Some scientists believe that as the temperature of ocean water rises, the box jellyfish’s territory could start spreading northward. Experts worry that if the box jellyfish moves into new coastal areas, more people could become victims of its deadly sting.

About BeeLine

About BeeLine