National Reading Month Highlights Urgency in Helping Students Amid Book Bans and Poor Test Scores

by Lexi Lonas

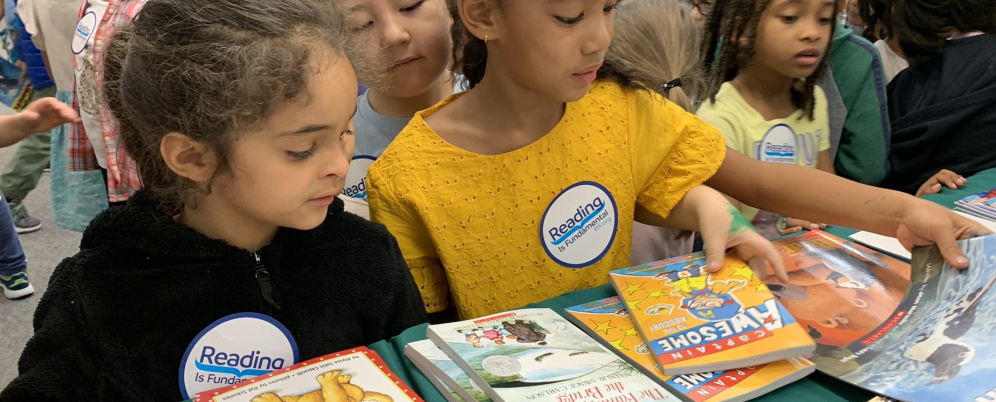

With National Reading Month nearly halfway over, advocates are highlighting the difficulties students face when it comes to getting a book in their hands and staying engaged with the content.

Reading, either for school or pleasure, has taken a dip for students from elementary to high school as educators and parents struggle to get them to choose books over social media — and navigate different instructional methods for reading at all.

Experts are focused not just on how to get students to read but ensuring they have a wide variety of options as book bans across the country refuse to abate.

“It’s certainly a complex time. You have the NAEP [National Assessment of Educational Progress] scores in reading at a 30-year low. A lot of people are rallying right now around the science of reading and getting more evidence-based reading instruction into schools. And, alongside that, the recent NAEP data showed that only 14 percent of students say that they read for fun every day,” said Erin Bailey, the director of literacy and content for Reading is Fundamental.

National Reading Month is celebrated across the country in honor of Dr. Seuss’s March 2 birthday, with schools and libraries creating challenges to encourage students to read more.

Bailey argues that difficulties with getting students to read start with two factors that are “interrelated”: low test scores and a lack of desire.

“In addition to students not being able to read proficiently, they also don’t want to read,” she said, adding, “Of course, you are not going to want to read for fun if it’s something that is difficult for you.”

The 14 percent of students who read for pleasure daily according to the NAEP is down 3 percent from 2020 and 13 percent from 2012. The latest report showed 31 percent of students never or hardly read for fun.

Blame for the decline in reading for fun often lands on phones and tablets, with Stanford Medicine showing back in 2022 that the average age of a child receiving their first phone has gone down to 11. In 2015, Common Sense Media had that number at 14.

“I do think we need to be more format-inclusive, so when we think about ‘What does it mean to read for fun?’ That may include reading a book, it may include reading an e-book on a tablet, but it also can be reading in different digital spaces, so maybe thinking about reading posts on social media also as reading for fun,” Bailey said.

But of course before students can be encouraged to read, they must first know how, and there has been growing focus at the state level on how exactly they are taught.

Dozens of states in the past few years have switched requirements for educators to teach the science of reading, which puts emphasis on phonics, or the ability to understand how letters go together and sound them out.

While the switch to the science of reading has been important, Susanne Nobles, chief academic officer of Read Works, argues there needs to be more emphasis on what happens after a student starts to understand phonics and word recognition.

“The most critical aspect of successful reading is knowledge and vocabulary,” Nobles said.

“I think it’s really important for teachers to think about that because” once a student can learn from a text, not just understand how to pronounce it, it “builds more knowledge and vocabulary to bring to the future reading,” she added.

And underlying other concerns during National Reading Month is the political fight over which books are available to children.

Numerous Republican-led states in recent years have taken books off classroom and school library shelves, largely ones that relate to race and LGBTQ topics.

While proponents of this move say it is to protect children from sexually explicit materials, critics counter that many students are being denied the ability to read about characters similar to themselves.

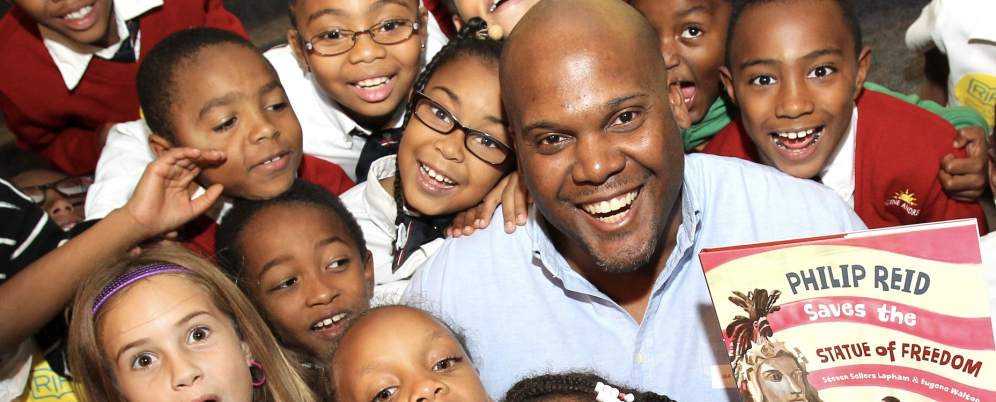

“I think that is front and center for this month, around how do we defend the right to read for students and how do we ensure that students have access to diverse and inclusive books in their classrooms and school libraries,” said Kasey Meehan, Freedom to Read program director at PEN America. “And I think we see this movement target certain types of books that include representations of LGBTQ+ individuals or Black and Brown individuals and families and histories. We need to ensure that suppression does not have a place in our public school classrooms.”

Between National Reading Month, Right to Read Day on April 24 and reading week earlier this month, experts say this is a time to recognize the task before educators and libraries and what might lie ahead.

“This springtime is a really amazing time to elevate the importance of reading and to reaffirm our librarians and our educators and our libraries and public schools in the job and the roles that they play in helping young people read,” Meehan said.

This article was originally published on The Hill. Learn more about the many ways RIF works to spread the joy of reading while providing books and reading resources to the communities we support nationwide by clicking here.